American education and how I learned about “tracking”

Yesterday (it’s past-midnight here, as I start writing this) I watched a documentary called “Waiting For Superman” by Davis Guggenheim. The documentary talks about issues in the American school system and how children are waiting for a Superman-like savior figure to rescue them from it. What is this so-called figure, according to the film? Rockstar teachers. I’m oversimplifying the plot of the film, but that’s basically it. The film, in my humble opinion, appears to be a huge ad for public charter schools, of which I remember my teachers in public government school speaking nothing but ill. However, one of the issues the documentary spoke to is “tracking.” You can see the clip from the film here:

Now that you have a rough idea of what tracking is, I’d like to explain how I experienced it personally.

A bit about my educational background

I began my school career in the schools of my district. I went to an elementary school that I was zoned to in Kindergarten and then my family moved. I then spent three grades in another elementary school to which I was zoned. Due to my love for performing arts, my mom thought it would be a good idea to enter me into the lottery to get into the performing arts magnet elementary school of my district (thank you, school choice fair). I was accepted and I transferred before the beginning of my fourth grade year.

It wasn’t easy being a transfer student. I didn’t like all of the kids I had to bus with to get to the school. Everybody else in my class already had their peer groups, but I found it difficult to make friends. I loved drama and the drama teacher, but she didn’t care for me too much, because I asked a lot of questions and… Well… She was just not a nice person. (She was put on probation for saying something profane to an administrator. She later left the school entirely.) At any rate, after a rough two last years of elementary school, I was ready for middle school and it was time to visit the performing arts magnet that my elementary school fed into.

I went with my mother and we were given a course sign-up sheet. From there, I could select several courses that interested me. I remember selecting beginning band, because I wanted to learn to play another instrument. If I remember correctly, sixth graders were only allowed one or two electives, whereas seventh graders get more choices. This was due to there being a block English and Reading course, which ate up two periods, next to the other standard Science, Mathematics, Social Studies, Physical Education (half-year) and a computer course (half-year, called Business Technology) that I just now remember taking.

The only other choice on that sheet, which wasn’t actually yours to make, was the level of math you were to take upon entering sixth grade. There were two options:

- 6M ___

- 7M+ ___ Teacher Signature ________

My mom looked at me and said, “I don’t think you need to go into 7th grade math, do you?” It was a sincere question. She didn’t understand why there were two choices and neither did I. I trusted my mom’s judgement and let her tick off the 6 math option. “Why was there only 7M+ anyway and no regular 7? Hmm…” Little did I know, that this simple tick would have thrown my educational career in a trajectory I wouldn’t have wanted.

My first sign came from a concerned look from my fifth grade teacher, Ms. Schroeder. She said, “Tyler, I think you could go into 7+ math. Are you sure you want to go into 6?” I, not being sure about who to trust; my mom or my teacher; just told her, “no, it’s fine,” and that was that. I soon realized why I should have listened to my teacher.

6M

I won’t say that I was a genius at math, but until 6th grade, my worst weakness in math was long division. My well-meaning 6th grade math teacher was a nice man and often poked fun at the students in a playful way. He knew what he was talking about and he was able to keep control of the classroom well. However, I found it very difficult to learn from him and I struggled. Not just for academic reasons, though.

A lot of the kids in my math class were “bad kids.” I remember some of them sitting next to me during group work. I was diligently trying to explain how to solve a problem to them when one kid sucks his teeth and says, “man, we don’t care about that. I just want those answers.” Going up to the overhead projector was a bit nerve-wracking for me and I remember my classmates making fun of me for the way my hand was shaking as I tried to write out a problem. I was just afraid of getting it wrong, was all, but their laughter only made it worse.

Middle school wasn’t on “medium mode”

It also became very challenging for me to balance home life and school life. I just started getting addicted to the computer and I was trying to master the art of Flash animations (I never did). I talked with more people online via MSN Messenger than I did at school and I spoke with more kids from school on AOL Instant Messenger (AIM) and MySpace than I did at school! Also, juggling multiple assignments from different teachers, forgetting what was assigned or losing papers was a constant source of stress. I remember getting one detention at school and that was for forgetting to bring my viola from home. (Joke’s on them. I never took it home again and thus ruined my chance of becoming a prodigy.) In short, I was a disorganized mess. If an assignment wasn’t obligatory, I never did it (I’m thinking of Mr. Ragon’s science study guides, in particular). If it was obligatory, I often did it very last-minute. I still managed to keep good grades in most classes, due to the fact that I did in-class work well and did well on exams. Except, in math.

A failure?

My grades began slipping in math and I didn’t even know it. Sometimes, it was the result of a quiz, sometimes, it was because I forgot to turn an assignment in, but those little Fs in the gradebook accumulated as a big F on my mid-term report. I remember sitting there with my mom and my teacher called us up. He asked me what grade I thought I had gotten and I said, “a B.” He then, probably while resisting the urge to laugh at the irony, revealed the F on my mid-term report to my mom and to me. I was shocked. I never got an F as a grade before. “Maybe I’m just not good at math,” was one of my thoughts.

Why I wanted to get into 7+

It was hardly the time for me to ask it, but I was naïve and stubborn, so I told my teacher that I would like to get into 7+ math the following year. My reasoning in my head was simple: that’s where all of the smart kids go. I figured that if I wanted to be with a lot of my friends (who just so happened to be there), I would need to catch up from behind, albeit one year late.

My teacher, however, was not convinced. I mean, I don’t blame him, seeing as I currently had an F in his class. He told me he thought that regular 7th grade math would be most appropriate for me. My mom, now faced with the reality that her son was pulling an F, agreed with him and saw no reason for me to want to go further.

Thank God I’m stubborn.

My plan

See, I was never afraid of going over someone’s head to get what I wanted. I consider it a special gift of mine that if I can’t get what I want from one person, I’ll find the person who can get it to me, on my terms. What did I want? To get into 7+ math the following year. Who could make that happen? The principal.

Mr. Brian Smith was a remarkable man. He was a good administrator, a friendly person, a supporter of the arts, a friend to the teachers, trustworthy, and helpful. I don’t remember how I managed to meet with him, but I did. I told him my concerns and I even told him about how my fifth grade teacher wanted me to get into 7+M as a sixth grader. He, hearing my case out, offered to speak to the head of the mathematics teachers. He did and I was to meet them during the Summer to take an assessment.

“He belongs in my class”

I went into the school the day of the assessment with my mother and I met the principal and the head mathematics teacher. I knew him only in name before from a time that one of the popular kids in school, a class clown 8th grader, mocked the way that he placed his hands on his hips as he peed at the urinal. “Hey, look, this is how Mr. (Math teacher) pees.”

I don’t remember exactly what was on that exam. I remember certain measurement conversions and converting irregular fractions to mixed numbers and vice-a-versa. I remember I was allowed to use a calculator for certain parts of the exam, which was helpful to make up for my deficiency in long division. When I was done, I handed the paper to the head math teacher for evaluation.

After only a few seconds of looking it over, he exclaimed, “he doesn’t belong in 7+M, he belongs in my class!” His class was Algebra, which was normally taught in 9th grade in our school system. If I accepted, I would effectively have gone from Tyler, the boy with an F on his midterm in 6M, to Tyler, the boy taking 9th grade math as a seventh grader. To me, the answer was clear. So long, bad kids. Hello, smart friends. My self-imposed poetic justice felt sweet. I accepted.

Not so easy, after all

While I could ace an assessment, classwork, as I soon found out, would be difficult in 7th grade Algebra. Our teacher (the aforementioned head) had a minimalist lecture style, which can be summed up in bullet points:

- Introduce concept

- Show examples on black board

- Ask if there are any questions about concepts shown

(We really wanted to say, “uhm, yes. Can you explain that again, like, maybe five times?” We kept silent instead.) - Assign book work

- Sit down at desk and contemplate teaching career

- Act hot and bothered if a student comes to you with questions about what was just shown

I realized that while he had faith in me being able to join his class, I didn’t have much faith in myself to make it through the class. And while, yes, many of my smart friends were in the class, they weren’t always free to help me. I didn’t live close to any of them, Khan Academy didn’t become viral until 2008, my parents weren’t good at math, and (worst of all) the “bad kid” 8th graders were still in Algebra.

Unfortunately, a lot of the other kids in the class were just as lost about the concepts as I was. So, with minimal help from the teacher and a lack of comprehension from many of the students, it was hard for me to get by. I somehow did, though. I managed to keep a B average in both 7th grade Algebra and 8th grade Geometry. To this day, I don’t know how I did it.

New school — new track

For several personal reasons, I did not want to attend the high school that my middle school would feed into. The main reason being that this high school was not very strong in the performing arts. So, using my stubbornness and persistence again, I managed to successfully transfer to a high school out of my zone. This high school, however, was not set up as a magnet school. It was just a regular high school with normal high school programs and where football was king. (I only somewhat regret to say that I never once attended a game.) However, the math program was different.

This high school, along with a few others, started experimenting with what is called the “block system.” This is where — like in my middle school English/Reading class — English, Math, and Science are all taken by the same students in one single block. There are two main ways, however that the blocks are divided. Obviously, to limit class size, each block only had a maximum of around 25 students. But secondly, the blocks were separated by performance. There was the Honors block and the Academic block. And what, pray tell, was the deciding factor in separating one from the Honors block?

GPA? Nope.

Score on state assessment? Nope.

IQ? Nope.

EQ? Nope.

That’s right… The main factor of determining your classes for the next 4 years was whether or not you already completed Algebra in middle school.

“But, Tyler,” you may be asking… “didn’t you not only complete Algebra, but Geometry, as well?” Indeed, that is true. However, the high school I transferred to did not have a block for allowing freshmen to take Algebra II in their freshman year. Also, it turns out, that even though I passed Geometry in the eighth grade, I did not score “high enough” on one of the midterm state assessments, and was thus required to take the entire course again! Yes, let me reiterate… I passed the course but I did not pass the state assessment, thus, I needed to take the entire course again! This unfortunate situation, like my situation in middle school, caused me to be cranky and less-motivated to work hard in math.

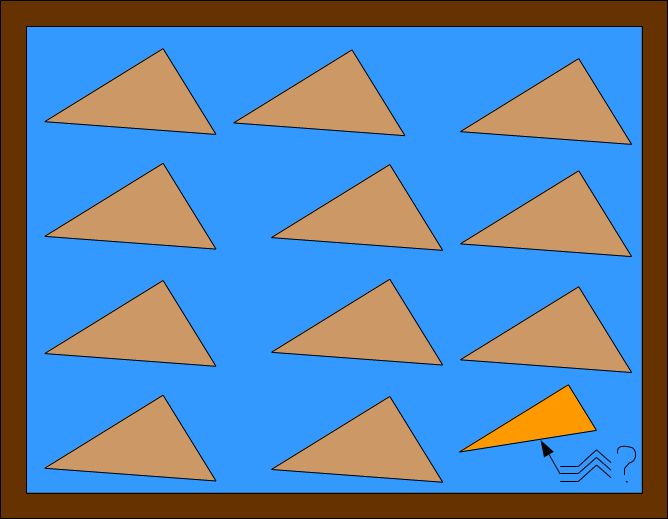

One of my most embarrassing memories was when we had to use a protractor to construct triangles. The triangles were to then be tacked onto the wall (with no names on them) to show the uniformity. I don’t know what was going through my head or how I did it, but my triangle looked absolutely nothing like everyone else’s. Let me illustrate roughly how it was.

next to my triangle, the teacher wrote “<– what is this?,” which still haunts me to this day.

So, I was never really an all-star at math at this point. I found it very hard to grasp more abstract concepts and I didn’t put much effort into studying when I got home. Again, my computer addiction took precedent.

The silver lining, however, is that I was able to stay in the honors block (I maintained an A-B average), which then led me into taking AP courses my junior and senior years. While I didn’t get a 5 on every AP exam, AP courses automatically raise your GPA. So, a B in an AP course is more like an A in a regular course. I was also able to stay together with highly-motivated friends, which definitely helped my motivation in school.

Who would have thought, if I didn’t try to fight back against being put in regular 7M all those years before, that the entire course of my high school career would have been different. While I wasn’t happy about taking Geometry again and while I didn’t get the best grades in high school Math, it was worth it to stay in the higher track.

Final thoughts

I think about all of the kids, however, who weren’t the “bad kids” back in 6M. Indeed, there were other good kids who worked hard at school and just found math to be a difficult subject. Were they forever stuck in the Academic track, all because of math? I get that there can’t be too many different block types and I understand why they wanted to utilize a block system. Having all classes with all of the same kids for a year definitely made a difference in our high school social lives, because we all knew each other.

But what about the boy who is a whiz at Biology and terrible at Math? Why should he be held back with the under-performing children, just because he didn’t take Algebra in eight grade? Same with the girl who is an avid reader and writer and can analyze the themes in Great Expectations with ease, but can’t figure out sin, cos, and tan to save her life? Why make Math the cut-off?

Maybe one of my teachers will see this and answer, some day.

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

I agree. Education system needs to look at the whole person and allow for variations in students gifts or weaknesses in one area or the other, and allow individual progress. Also teachers need to be more aware and caring about their students and how they learn.

I didn’t know all of this struggle/ situation in your life. I was just aware how intelligent and gifted you are in many areas.

I still remember standing at the chalkboard in tears during 7th grade algebra crying as the teacher berated me for not understanding. Some people are not meant to teach. Good teachers are worth their weight in gold.